actually, you do have a choice

You just don't like the price

Sometimes, I catch myself saying things that rob me of the very power I say I want:

“I don’t have a choice.”

“If I don’t, who will?”

“If things were easier, I might have done that.”

In the moment, the words feel justified. On replay, I wince. I wince because the truth is this: I almost always have a choice. I just don’t like the associated price tag.

I think a similar thing is true for most people in my circle. We could quit the job without a backup plan. But we need to be okay with facing the cost of an unstable income when there’s rent to pay. We could leave the relationship that’s not serving us. But we need to be okay facing the emotional hangover of starting over. We could commit to the unconventional path: quit the prestigious career, move out of the city, marry the unsuitable person. But we need to be okay with possibly disappointing the people we’ve spent our lives pleasing, being misunderstood, maybe even being judged.

As the economist Thomas Sowell said:

“There are no solutions. Only trade-offs.”

Sowell was describing how governments allocate limited resources across competing societal goals (e.g. defense vs. education vs. healthcare). But I think the same is true for many decisions in our lives, both big and small.

The real question isn’t “What is the solution?” It’s “What are the trade-offs?”

And relatedly,

(a) How aware am I of the trade-offs?

(b) And how willing am I to own the consequences of making that choice?

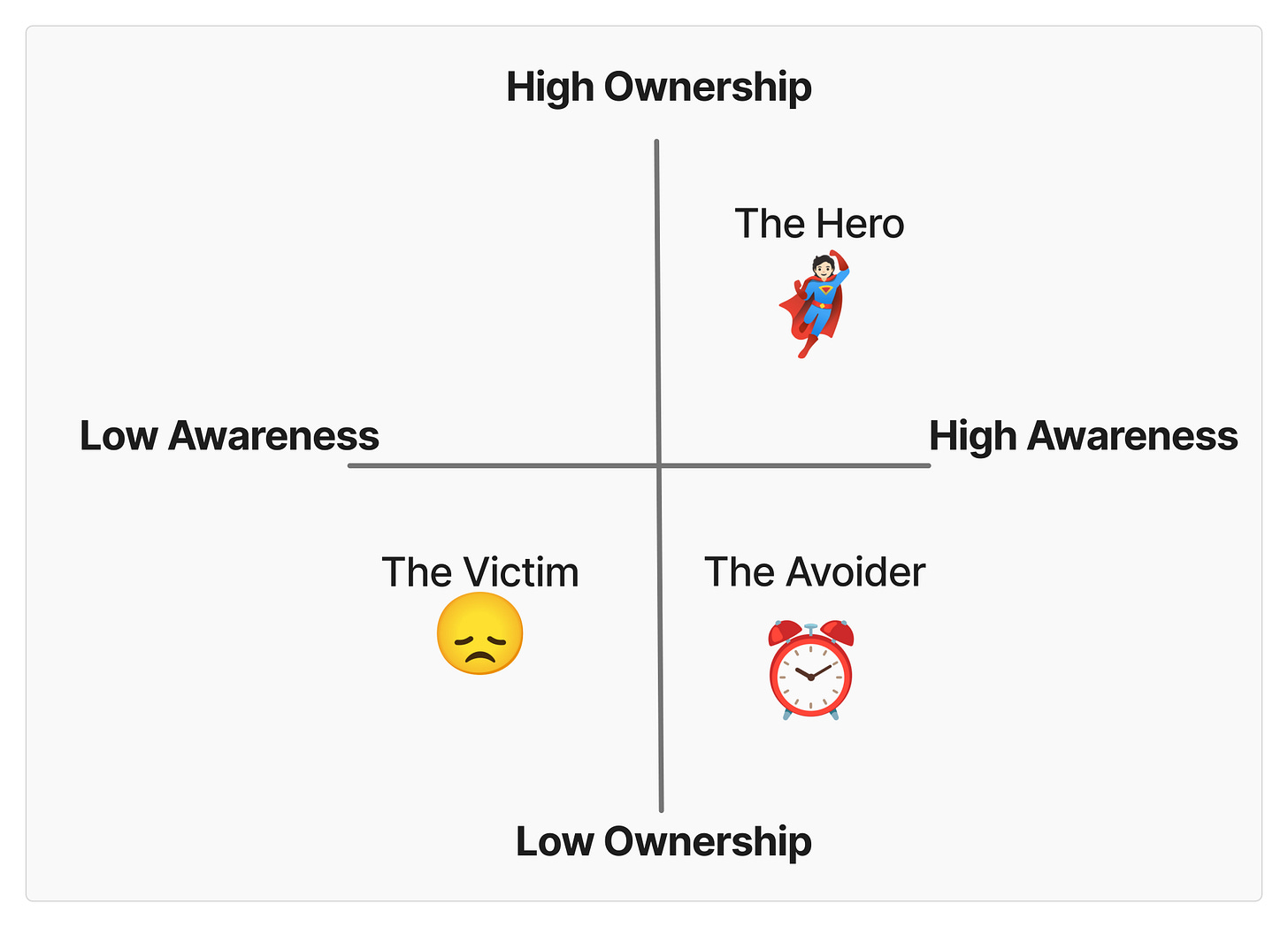

Realizing this has helped me understand the different archetypes I cycle between when I use the language of “choice”.

1. Archetype 1: The Victim:

This is when I'm not aware of the trade-off and don't take ownership.

Internal dialogue = “well, I guess I have no choice.”

2. Archetype 2: The Avoider:

This is when I'm aware of the trade-off but delay/avoid the choice.

Internal dialogue = “I’ll decide later”.

3. Archetype 3: The Hero:

This is where I aspire to be. These are the moments when I fully acknowledge the trade-offs I face and take ownership of my decision.

Internal dialogue = “I accept the consequences of this decision, whether they’re good or bad.”

Before we explore these archetypes further, an objection: younger me would probably scoff, “That’s easy for some to say. Not everyone can afford to be the hero” and accuse anyone making these claims of privilege.

And to some extent, the privilege objection is valid. Some people live in environments that actively restrict their choice - economic disparity, war, authoritarian regimes. Some people are born into softer landings - the safety net of generational wealth, or the reassurance of knowing someone will catch them if they fall.

So yeah, sadly choices aren’t created equal. But, to say we have a choice isn't to deny inequality or oppression — ugly truths about the world more real than my privileged life will ever know. But to say we don't have choice does deny our agency.

With these caveats in mind, let’s meet The Victim.

(1) The Victim

When I recoil into victim mode, “I don’t have a choice” usually means “I’m scared of the consequences of choosing X over Y” or “I don't want to admit that I need to pay cost Z if I choose X”.

I think we all sometimes recoil into victim mode because it’s easier to make no decision than to be responsible for the wrong decision. So, instead of confronting the cost, we tell ourselves a more comforting story: we don’t have the agency to make a decision, thanks to feature #42 of this broken system or courtesy of person #7 in our lives who’s overstayed their welcome.

But costly is not the same as unavailable. When we live as The Victim, we don't just lose our agency, we also lose our story. We become side characters in our own lives.

(2) The Avoider

When I’m in Avoider mode, I recognize the trade-off but I’m paralyzed by overwhelm and analsysis. I say “I’ll decide later” or “I need more information”. I’m not denying I have a choice. But I’m sort of putting it off until the decision makes itself?

Sometimes, my Avoider-self becomes The Delegator. I pass the responsibility of choosing to someone else. “What do you think I should do?” “I trust your judgement more than mine”. “Maybe I should speak to a professional”. This is also a form of avoiding because it creates the opportunity to shift blame to the delegated decision maker.

What my Avoider-self doesn't realize is that every choice has a price - even the choice to do nothing. Jean-Paul Sartre once said, “I can always choose, but I ought to know that if I do not choose, I am still choosing.” And therein lies the Avoider conundrum.

“Opportunity cost” is the term economists use to describe the value of the alternative option that you don’t take. Just because opportunity cost is invisible, it doesn’t mean it’s cheap. In fact, those might be the most expensive choices of all because it slowly creeps up on you without you realizing.

(3) The Hero

Ah… now, The Hero. This is the archetype I aspire to be and fall most short of. The hero fully acknowledges both trade-offs and personal agency, acting intentionally within constraints. Their perspective is “Given these circumstances, I'm choosing this path” and “I accept the consequences of this decision.” And in so doing, they experience authentic ownership of life - both the highs and the lows.

When we expand and step into Hero mode, we’re aware of the costs of our choices and actions but we make the choice anyway. We may be aware of all the ways in which our choices are constrained, but - as James Hollis (quoting Jean-Paul Sartre) says in Living An Examined Life says - we:

"act as if we are free, take on the “terrible” burden of choice, and be accountable"

The Hero archetype is not about doing extraordinary things. The Hero isn't fearless. They're just willing to accept fear and potentially negative consequences as the price of authorship.

~~

I like to think that the shift from victim to hero isn't an overnight transformation but a daily practice. Sometimes, it’s small and simple: “I need to work late; I don’t have time for the workout” to “I'm working later this evening, so I'll get up 30 minutes earlier so I can squeeze in a quick run”.

Sometimes, it’s big and scary: “I’ve invested 5+ years in this relationship/ career/ city already, I have no choice but to stay“ to “It’s okay to give myself the permission and the time to restart from zero”.

Most days, we'll fail. The blanket of “no choice” will be too warm and comforting to climb out of. But some day, with practice, we’ll turn from secondary characters into active authors of our lives.

—

Ines

Why do you keep writing pieces that just make sense??

Also appreciate your caveat on this "to some extent, the privilege objection is valid. Some people live in environments that actively restrict their choice - economic disparity, war, authoritarian regimes. Some people are born into softer landings - the safety net of generational wealth, or the reassurance of knowing someone will catch them if they fall."

My friend & I were catching up last week and chatting about our life decisions on choosing to continuously show up for our biological families even though they're not 100% ok w our queerness, and just acknowledging that we made that choice conacioislt also gives us a sense of agency.

He said "we don't have the same 24 hours as other people" bc we spent our early 20s reconciling w the hurt, the homophobia etc so while we watched our friends have skyrocketing careers, we were a bit too preoccupied w our own internal work in that early years 😂🙈 not to say that this is an excuse for being a victim. But being the hero looks different on everyone. And I think you were able to show that quite nicely here without being condescending on the other archetypes :)

I'd agree that we have to take ownership of our lives. In other words, we do have agency—to a certain degree.

I don't know much about physics, but we could use the analogy of Newtonian classical mechanics and Einsteinian relativity.

The argument the older you is making fits perfectly with classical mechanics, whereas the argument the younger you made is looking at the broader universe of the theory of relativity.

When we're younger, we look to create a new and more just universe. As we get older, we have less time left, so we seek a more practical philosophical approach—one that will concretely improve our lives—and we lean more Newtonian.

But we can't lose sight of the relativist in us. We need it to drive us forward.