my CV of "failures"

The case for documenting things that didn't work out

In my second year of grad school, a friend told me about a Princeton professor who publishes a “CV of failures” on his personal website.

I’d just received my first rejection after submitting a paper to a journal and I was disappointed. This friend thought I’d feel better after seeing a successful professor’s failure (bless her!).

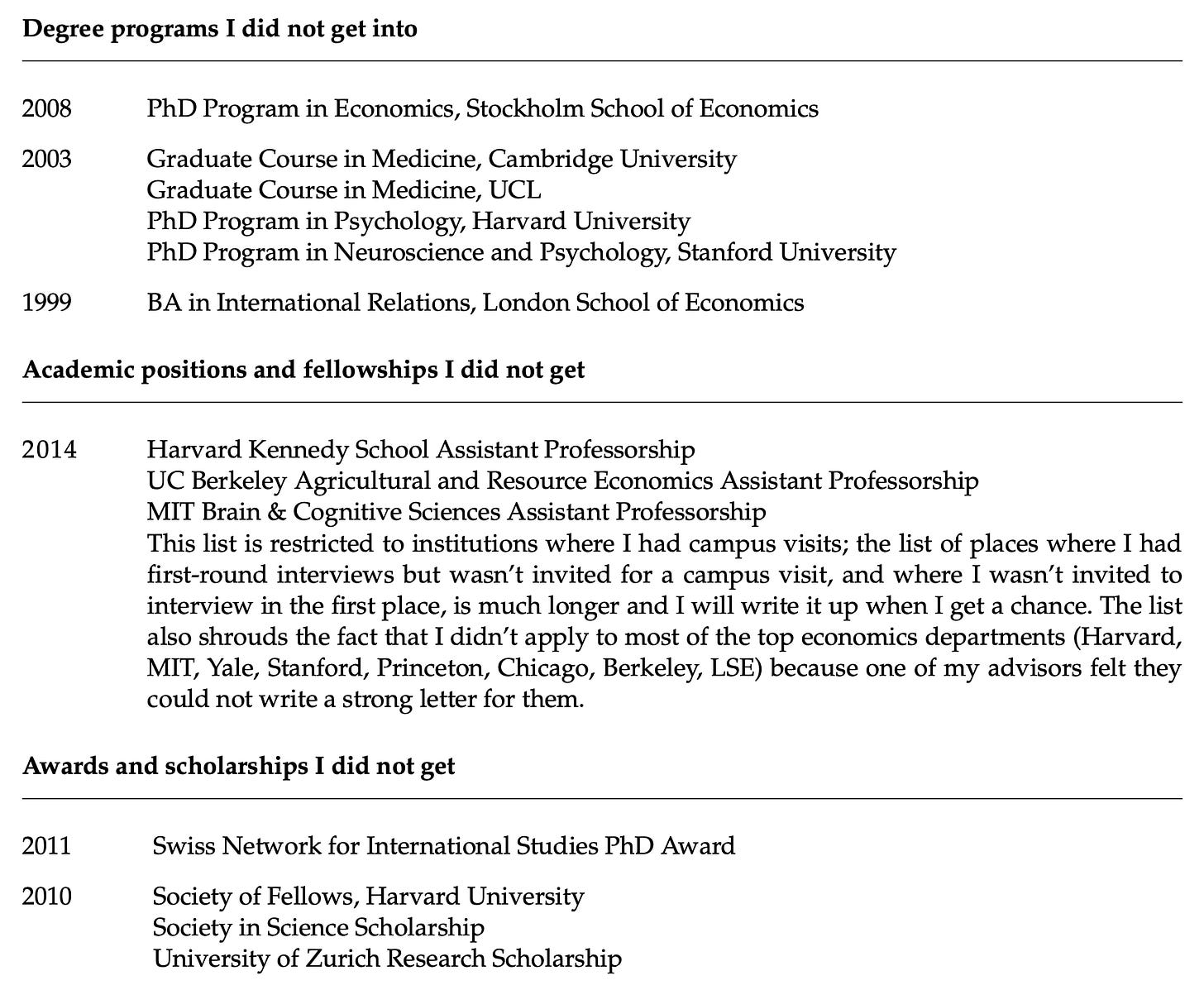

In his CV of failures, Prof. Johannes Hausaufer documents significant things that didn’t “work out”: degree programs he didn’t get into, academic positions and fellowships he was rejected from, journal rejections, research funding applications that he never heard back from, awards and scholarships he didn’t receive. And more.

He explains why he made the CV public:

“Most of what I try fails, but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible. I have noticed that this sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me. As a result, they are more likely to attribute their own failures to themselves, rather than the fact that the world is stochastic, applications are crapshoots, and selection committees and referees have bad days.”

The CV went viral, with coverage from the BBC, the Guardian, and other big media outlets. At the bottom, Prof. Johannes added a final entry under Meta-Failures:

“This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention than my entire body of academic work.”

I laughed out loud in the library.

(I’m usually not one to take pleasure in another’s rejections, but my friend wasn’t wrong: After seeing this CV of failure, I was feeling quite a bit lighter about the rejection I received earlier.)

To be fair, Prof. Johannes’ “failures” are... impressive. Rejected from Harvard and Stanford, sure, but he landed at Princeton. Five papers rejected from top journals, but plenty more published.

Still, it was a good reminder that everyone we admire had a document like this, a “shadow CV” of sorts that recorded all the times they’ve gotten a “thank you, but no thanks”.

The Problem of Survivor Bias

The opposite of a CV of failure is survivor bias: the tendency to see only success stories while failures remain invisible.

We live in a world of survivor bias. We see and hear about successful outcomes, rather than failed attempts.

Aspiring authors see the success of Harry Potter - the books, the films, the theme parks - but not the 12 publisher rejections J.K. Rowling endured before one finally said yes.

Aspiring athletes see Steph Curry’s brilliance on the court, but not the 98.8% pro college basketball players who don’t make it to the NBA.

Aspiring entrepreneurs see Instagram’s $1 billion acquisition by Facebook, but not the hundreds of photo-sharing startups that failed doing similar things.

Our very online era has turned survivor bias into a structural problem. Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook are survivor bias machines. Algorithms favor engagement, and engagement skews positive. So, we see diamond rings and engagement announcements (not breakups). We see book deals (not rejections from 47 agents). We see funding rounds (not the 9 out of 10 startups that fail in their first decade).

The result is that we feel like we’re failing alone.

But that’s not all. I read a study recently that suggests survivor bias doesn’t just make us feel bad when we fail, it makes us perform worse.

In 2016, researchers at Columbia ran an experiment with 402 high school students. The students were studying famous scientists like Einstein, Marie Curie, and Michael Faraday. They were split into 3 groups.

Group 1 read about the scientists’ achievements: Nobel Prizes, groundbreaking discoveries, brilliant insights.

Group 2 read about their personal struggles: Einstein fleeing Nazi Germany, Curie facing poverty and discrimination.

Group 3 read about their intellectual struggles: failed experiments, wrong hypotheses, years of dead ends before a breakthrough.

After six weeks, the researchers measured the students’ science grades. The students who read about struggles (personal or intellectual) significantly improved their grades. Low-achieving students benefited the most. Students who read only about achievements didn’t just not improve. Their grades actually dropped compared to before the study

My understanding of these results is that when we see polished success, we don’t just feel inadequate, we might try less hard too. We assume success requires a kind of genius we don’t possess, so we play it safe. We don’t apply for the stretch role. We don’t submit to the prestigious journal. We don’t start that ambitious project.

As lead researcher Xiaodong Lin-Siegler explains:

“When kids think Einstein is a genius who is different from everyone else, then they believe they will never measure up. Many students don’t realize that all successes require a long journey with many failures along the way.”

WW2 Planes & The Case for CV of Failures

What if more people - especially published authors, funded founders, promoted executives, tenured professors - documented their failures the way Prof. Johannes did?

The case for a public CV of failures seems clear. When you share your failures, you help everyone behind you recalibrate their expectations. You normalize struggle. You play a part in correcting survivor bias at scale.

But not everyone can afford to share their failures publicly. Prof. Johannes could publish his CV because he had tenure at Princeton. His professional position was secure. The same can’t be said for the junior employee worried about looking incompetent, the job seeker concerned a public record will hurt their prospects, or people from marginalized groups who already face more scrutiny.

I think, however, that a private CV of failures is still valuable because it gives you a fuller picture of yourself.

During WWII, the U.S. military analyzed bomber planes returning from combat missions. Bullet holes clustered on the wings and tail. Their conclusion seemed obvious: reinforce the wings and tail.

Then statistician Abraham Wald stepped in. He said: Guys, you’ve got it backwards. Armor the engines - the places with no bullet holes.

Huh? Wald’s observation was that the military was only analyzing planes that survived. The bullet holes on wings and tail showed where planes could take damage and still fly home. A reasonable assumption seemed to be that the planes hit in the engines couldn’t make it back. That’s why there were no bullet hole in that area on the returning planes.

The key point: “missing” data matters when figuring out the next best step forward.

The same applies to your life. Your regular CV shows the “returning planes” - the jobs you got, the degrees you completed, the projects that succeeded. But it doesn’t show where you actually got hit. The 23 applications that went nowhere. The failed courses. The abandoned projects.

Your CV of failures shows the “missing planes” - the jobs you didn’t get, the projects you dropped halfway, maybe the relationships that didn’t work out.

Combined, the two CVs give you more complete data about yourself. It shows not just what succeeded, but what you tried. Where you’re vulnerable. What brought you down. What you survived.

My CV of “Failures”

In this spirit, below is a partial list of my professional failures in the past decade. (My private list is much longer and more detailed but here’s a taster anyway!).

There are plenty of personal failures I could include - abandoned projects, dropped habits, relationships I could have handled better. But… that’s for another time and space. The one personal failure I included is taking waaaay longer than average to pass my driving test because that’s too embarrassingly memorable not to include.

Here we go…(in reverse chronological order):

2025 Spring/Summer | After leaving my previous job, I considered returning to academia and research. Applied to multiple positions. Got nowhere. Eventually decided to pursue the entrepreneurial/ self-employment path (for the short term?) Some of the things I applied to and got rejected from:

Fellowship applications: 2 applications → 2 rejections

Research/policy jobs: 7 applications → 6 rejections (and one I never heard back from which probably means no)

Editorial/writing positions: 4 applications → 3 rejections and 1 acceptance (which I moved forward with on a contractor basis)

+ Many more that I’ve already forgotten

2020-2024 | Academia years. The journal and grant rejection machine starts churning…

Journal submissions: Over 60 journal applications → Over 50 rejections → Published 8 papers

Grant applications: Over 20+ research grant applications → Over 10 rejections → 5 successful applications for “medium-sized” grants (£5k-25k)

2019 | Final PhD Years

Applied to 9 post-doc / research positions → Rejected from 8 → Accepted to 1 at Cambridge (Felt lucky at the time. Feel even luckier in retrospect. Turned out to be the most transformative job I’ve had in many ways)

Rejected from a writing internship at The Economist (after making it to the final round)

2015 | Start of Graduate School

Really struggled in the first year of Economics grad school → Had a miserable time and considered dropping out. We somehow made it, baby!

Applied to 5+ Economics consulting summer internships (NERA, Oxera, Bain, LEK, etc) → Rejected from all

2014 | Finishing undergrad and started to think about grad school and jobs

Applied to a bunch of grad schools → Rejected from 6 graduate school programs; got into 1 program, which I accepted.

Summer internships: Over 20 applications → All rejections

Failed my driving test 3 times (I know…) and finally passed on the 4th (thank you, Ba, for the additional driving lessons and sorry for the raised blood pressure levels)

Your Turn

If you feel itched to create your own version, great!

Open a document.

Title it: “CV of Failures” or “Things I Tried” or “My Shadow CV”

Use one of these methods and start

Work backwards from your current CV. Open your traditional CV. For each success, ask: what’s not showing up here? Add a column listing the failures behind each achievement (the applications rejected, the programs you didn’t get into, the attempts that went nowhere).

Brain dump: Write down every failure you remember from the past 5 years - jobs you didn’t get, projects that flopped, skills you quit learning. Don’t organize or explain, just list.

Keep writing.

Don’t censor. Include the embarrassing failures, not just the “respectable” ones.

Don’t narrativize (at least not yet). Just document what happened. Resist the urge to turn every failure into a lesson learned. You can reflect later.

Do keep it private (for now). You can always share later, but start by writing it for yourself.

—

Ines x

Getting a behind-the-success look makes the journey more relatable, helps manage expectations, teaches you not to be hard on yourself, and motivates you during tough times.

I'm glad you wrote a full post on this after the post you shared in October. My relationship to "failure" has changed a lot since my close friend committed suicide a year ago. Confronting his death, and how we were both bullied in high school, made me reframe what was truly a failure and what was something to be proud of. Also, as someone in-between academia / private sector your post resonated.

One interesting question left unsaid with the exercise, and perhaps it is impossible, is when you get something you wanted in your career, but it was a wrong move: does that go on the success or failures side?

Anyway, thanks again for this post and the earlier note.

Leaving here for people interested in CV rewriting exercises: My related but different resume-rewrite is doing a CV based on what you're proud of, rather than what would impress a stranger, and I appreciated your kind comments about it on the note you shared in October.

https://poetryculture.substack.com/p/the-quiet-cv