In 1991, in her late 20s, my mother traded her job for a different kind of life. She was expecting my older sister, and in Southeast Asia at the time, that meant one thing: becoming a full-time mother.

She didn't go back to work. Instead, she dedicated the next few decades of her life raising five of us. A twelve-year spread from oldest to youngest meant there were always young children in her life. Through it all, she moved with a grace that made it look effortless. She taught me to read and write English; came to every swimming lesson; made sure we had packed lunches; patiently practiced scales on the piano even when our tempers frayed. She’d never raise her voice, though I’m certain there were many, many hair-ripping moments.

It wasn’t until my late 20s - probably a similar age to when she was expecting my older sister - that I asked my mother whether giving up work was a conscious decision.

“I don't think I thought that much about it. It was just what people did - at least if you had the option to. If you had the option to and didn't choose to stay at home, it probably reflected badly on you because you're prioritizing career over baby.”

Looking around at the women in my extended family and those of my mother's generation and cultural heritage, I could see her point. For them, becoming a wife and then a mother was the destined path by your mid-20s. What you saw was what you became.

The Motherhood Penalty

I’m not a mother (yet). If and when I do become one, I think I’d feel strongly about not giving up my career (at least, not entirely). And I've been thinking, wondering whether this is possible without something giving.

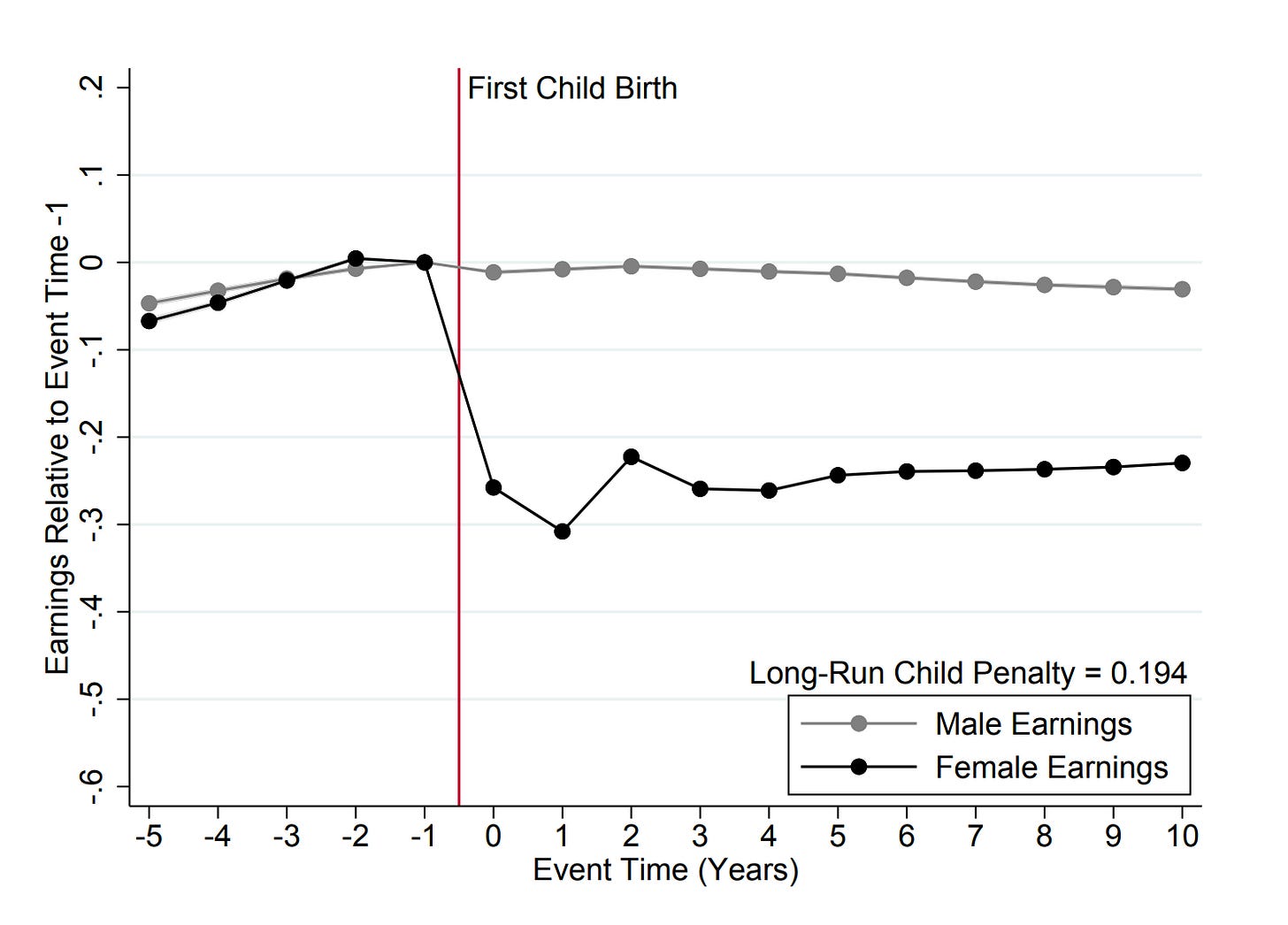

In my second year of graduate school, I took a labour economics class. I don't remember much of the curriculum but there's one graph that's still seared into my memory:

The lecturer explained what we were looking at.

“Let's now turn to this new paper from Henrik Kleven and co-authors. These Scandanavian guys have amazing data by the way. So they were able to track what happens when couples have their first child.”

He pointed to the red line marking the arrival of the first child. The black dots showed female earnings; the grey dots tracked male earnings. The pattern was stark: women's earnings plummeted after childbirth and stayed permanently lower, even a decade later. Men's earnings continued their steady climb, barely registering a blip.

The class split into two camps.

The first group saw elegant methodology - clean data, robust analysis, statistical significance. (For the record - I understand this view. To me, papers like this represent the best of economics - amazing data to tell a truth about the world)

They looked at the graph and said things like “Well, I guess it sort of makes sense. They can't both take a hit to their earnings if they're raising a family. It's good that at least the man's earnings are stable.”

The second group saw something more personal: a graphical representation of dreams deferred and choices constrained.

“You're missing the point. Why does it have to be the woman? And why does it have to last for more than a decade after the kid is born!? Also, if this is happening in Denmark - an egalitarian country with generous maternity leave! - what hope does the rest of the world have?!”

Since that 2019 paper, researchers have documented this “motherhood penalty” across 134 countries - the systemic loss in salary, benefits, and workplace opportunities that women experience after becoming mothers. Denmark's numbers, it turns out, were “good” compared to other nations.1

“Most countries display clear and sizable child penalties: men and women follow parallel trends before parenthood, but diverge sharply and persistently after parenthood,” the researchers write.

It's not about the money

Let’s get this straight: To me, this isn't about dollars and cents. I don't think this is even primarily about income.

To me, it’s about the (unequal) opportunity to express other sides of yourself beyond your family. It’s about the quiet erosion of parts of yourself. It’s about the forced choice between nurturing a career and being the kind of mother you imagined coming.

I see it in my friends who’ve become mothers. Their stories aren’t captured in the economic graphs. But they’re written in the apologetic texts they send when missing another dinner plan, written when they leave the board meetings to bump breast milk in the bathroom stalls, or when they take the part-time route because their husband’s hospital shift couldn’t flex.

One put it perfectly: “The problem isn't that I can't do both. The problem is that I can't do both without feeling like I'm failing at one or the other.”

This is what those clinical graphs in economic journals don't show: the invisible tax on a mother's spirit. The constant mental calculations. The perpetual sense of shortchanging either your professional ambitions or your maternal instincts.

But why?

Why, decades after women entered the workforce en masse, does the motherhood penalty exist?

There are broadly 3 competing theories for the main driver of the motherhood penalty.

(1) The easy answer would be biology. It's a comfortable explanation to think that nature simply designed mothers to prioritize children over careers. But the data tells a different story. Here's the evidence for why it doesn’t explain the full drop:

Differences across countries (details in a footnote): I'm no biologist. But I'm pretty sure the biology between mother and child is the same in the UK and Norway. Yet, the motherhood penalty is 34% in the UK and 3% in Norway.

Differences between adoptive vs biological mothers: When researchers look at the motherhood penalty for adoptive vs biological mothers, they find that in the short run the penalty is larger for biological mothers (which suggests biology matters in the short run due to things like breast feeding) but the long run penalty is pretty much the same. If biology explained everything, we’d see a much bigger difference between biological and adoptive mothers - yet they face similar penalties in the long run.

Differences between homosexual and same-sex couples: When researchers compare heterosexual couples and same-sex (female) couples, they find there is a drop in income for both partners and a bigger drop for the partner who gives birth. But the mother who gives birth catches up with her partner around 2 years after birth. From that point on both mothers experience similarly sized child penalties, which decrease over time until there is no longer a child penalty 4 years after birth.

(2) The next culprit seems obvious: policy. The theory here is if only we had better maternity and paternity leave, more flexible hours, more supportive systems etc etc…, then the gender disparities postpartum would disappear. I personally thought this could be the main driver. But the evidence suggests it's not.

In this 2024 paper, researchers look at the effect of family policy reforms in Austria (penalty: 34%) since the 1950s and see how it affects the dynamics of male and female earnings. Their conclusion: “Our results show that the enormous expansions of parental leave and childcare have had virtually no impact on gender convergence.”

In another very recent paper, researchers use data from Norway to study the impact of paternity leave and see whether this policy decreases the child penalty (by making caregiving more equitable). Their finding is both humorous and heartbreaking. Given the chance to take paternity leave, fathers overwhelmingly chose to take it... drumroll... during summer holidays, when their children were already in structured daycare programs.2

(3) Which brings us to the final, most unsettling explanation: it's in our heads. Or more precisely, it's in our social fabric. As of 2025, this seems to be the most convincing explanation to date.

In an elegant paper by Henrik Klevin called “Child Penalties and Parental Role Models: Classroom Exposure Effects”, the researchers find that if you went to school with kids whose mothers managed to balance both motherhood and a career, the motherhood penalty that you experience when you become a mother is much smaller.

In other words, the parental role models you’re exposed to when you’re an adolescent heavily shape actual gender gaps in the labor market decades later. They write “Our findings provide strong support to the idea that preference formation, social norms, and culture are crucial for shaping child penalties and therefore gender inequality.”

~~

I have no doubt my mother would have made an excellent working mother. For decades (imagine!), she juggled the after-school activities of five kids at different schools, tracked our medical appointments, helped with our paper maché projects while planning next week's groceries and meals. Her capacity to hold multiple spinning plates in the air (without a hint of frustration or struggle!) says to me that she'd have been an absolute boss lady in any corporate boardroom —graceful, kind, yet firm.

But she was expecting her first child at a time and place where being a working mother wasn't just uncommon – it was probably not recommended (at least if you had the option not to). And as the research shows, our sense of what's possible is profoundly shaped by what we see around us.

Sometimes, I wonder about the parallel universes where different choices were possible. Maybe in one version, she stopped after her second child (me), never meeting the three wonderful humans who would become my younger siblings. Or maybe, in another version, she found a way to keep one foot in her career, discovering another side of herself beyond our home's walls.

My mother is the most “things are what they are, let’s make the best of it” person I know. Give her thorns, she'll find roses; give her roses, she'll tend them with grace. I don’t think she wonders “what if?” about her career.

But I wonder. Not because I wish her life had been different, but because I feel strongly that she deserved, deserves, that choice. And because I wonder whether my or my sisters’ future daughters will someday read this piece and find it hopelessly dated - I hope they do.

—

Ines

Here's what the motherhood penalty looks like around the world. (If you fancy geeking out a bit, here's the website they've created to put together: https://childpenaltyatlas.org/

A few patterns to note:

(1) At a quick glance, we can see that Latin America, Australia, some parts of Europe, Iran/Iraq see very high levels of motherhood penalty. Norway (3%), Sweden (9%), Portugal (16%) are OECD countries with the lowest penalty.

(2) At low levels of development, child penalties represent a minuscule fraction of gender inequality. Places like Nigeria, Malawi, Mongolia, Vietnam, Laos, Mali, Niger see the lowest levels of motherhood penalties (1-3%) But as economies develop — incomes rise and the labor market transitions from subsistence agriculture towards salaried work in industry and services — child penalties take over as the dominant driver of gender inequality - Japan (44%), Germany (41%), Spain (36%), UK (34%), France (25%), US (25%), Canada (23%)s

(3) In some countries (Estonia, Finland, Austria), the motherhood penalty reverses so by the time your kid is 6 years old-ish, you've "caught up" with your spouse. In others (e.g. Greece, Italy, Malaysia), it gets worse - Earnings drop a little after birth. But by the time the kid is 8/9, the woman's seen a 50% drop in their earnings - indicating that they've dropped out of the labor market completely or transitioned to part-time work.

They write “Despite fathers overwhelmingly taking up this leave, we detect no impacts on child penalties. We additionally find no impact of paternity leave on the amount of leave fathers take for the next child, a good proxy for gender norms within couples. We highlight one possible explanation: fathers approach parental leave very differently than mothers. Fathers are much more likely to take their paternity leave during summer holidays, when their children are already in formal care, and take more part-time leave than mothers.”

This is such an important topic. My mother, un-conventionally chose to work, though I had never thought about how much "child penalty" she received. Looking back, I would say, a lot. But she worked on nevertheless, full time. Now that it is my turn, I have chosen to work part-time. I struggle to be the best in both worlds, but I stubbornly want to believe it is possible. I also want to fight for equality at work—to see myself as equal to my full-time colleagues—besides all the other inequalities of being a woman and a migrant. Yes, I like to climb very high mountains, but this is the only way to pave the way to a better future for my children.

When my mother became pregnant with me, she had to give up a work trip to Europe. She would never have that chance again because she left her job when she had my younger brother.

She never told me she regretted it. And in Southeast Asia in the 1990s, it was very possible to survive in a single-income household so the economics didn't play into her choice at all I don't think.

Now having been employed longer than she was, I don't know if I'd make the same decision.