for anyone worried about being replaced by AI

The Theory of The T-Shaped Professional

[Note: An updated version of this piece has been published on Every.]

You’ve probably been thinking about it. I know I’ve been, which means I’ve been thinking about how:

Over a decade ago, my undergrad professor Johannes hired me as a research assistant. Today, ChatGPT Deep Research can put together the literature review I was tasked with at a fraction of the time and cost.

During my econ PhD, I was a teaching assistant for a coding class. Today, that teaching assistant job probably doesn’t exist because students can learn to code much faster in a personalized way using AI.

In 2021, when I first started working behind-the-scenes in the creator economy, I’d type every word for a script, blog post, email and use raw brain power to come up with YouTube title ideas. Today, your favourite AI tool can do the same thing in seconds - and sometimes more creatively too.

So, I’ve come to accept that each year, some of the tasks that are currently integral to my job will become things that AI can do better - either alone (”AI replacement”) or in collaboration with me (”AI augmentation”). In other words, the value of some of my skills will decay. My guess is that anyone doing some form of knowledge work has grappled with this concern.

(There’s been an explosion of research on the effects of AI on jobs. My understanding of the literature is that the picture is a lot more nuanced than what the doomsayers or the AI-deniers suggest. In particular, (a) at the micro level, AI will indeed disrupt most knowledge work jobs, but (b) at the macro level, the effect on employment will be muted because industries and systems will adjust.)

The question I keep coming back to is this: In the age of AI, how should I be upskilling and retraining if the value of my current skillset is going to decay? And decay in a way that’s hard to predict?

One popular answer is to learn how to use AI. This is the foundation of the common refrain “AI won’t take your job, but someone using AI will.” But as Sangeet Paul Choudary argues in this brilliant piece, that’s quite a surface level response that neglects the broader repercussions of AI on system-wide shifts.

These days, there’s another answer that I keep coming back to. When asked by what kids should study in school these days, OpenAI CEO Sam Altmann said:

“Resilience, adaptability, high rate of learning, creativity, and certain familiarity with the tools.”

I keep coming back to this answer partly because, yes, it comes from one of the leading figures in the AI space. But also because I was expecting Sam to name a specific technical skills - like “AI engineering”. But he listed a broad range of meta-cognitive skills instead.

The more I think about it, the more it makes sense. AI’s black-box evolution means that no single skill is future-proof, so adaptability becomes the ultimate hedge.

This then raises another question. What does being adaptable even mean? Does it mean being a generalist rather than a specialist (as David Epstein argues in his 2018 (pre-ChatGPT!) book Range)? Does it mean being a polymath like Da Vinci?

I. Jobs, Tasks, Systems

Before we discuss what it means to be adaptable, let’s talk about what a job actually is (since many of us are probably thinking about adaptability in the context of work).

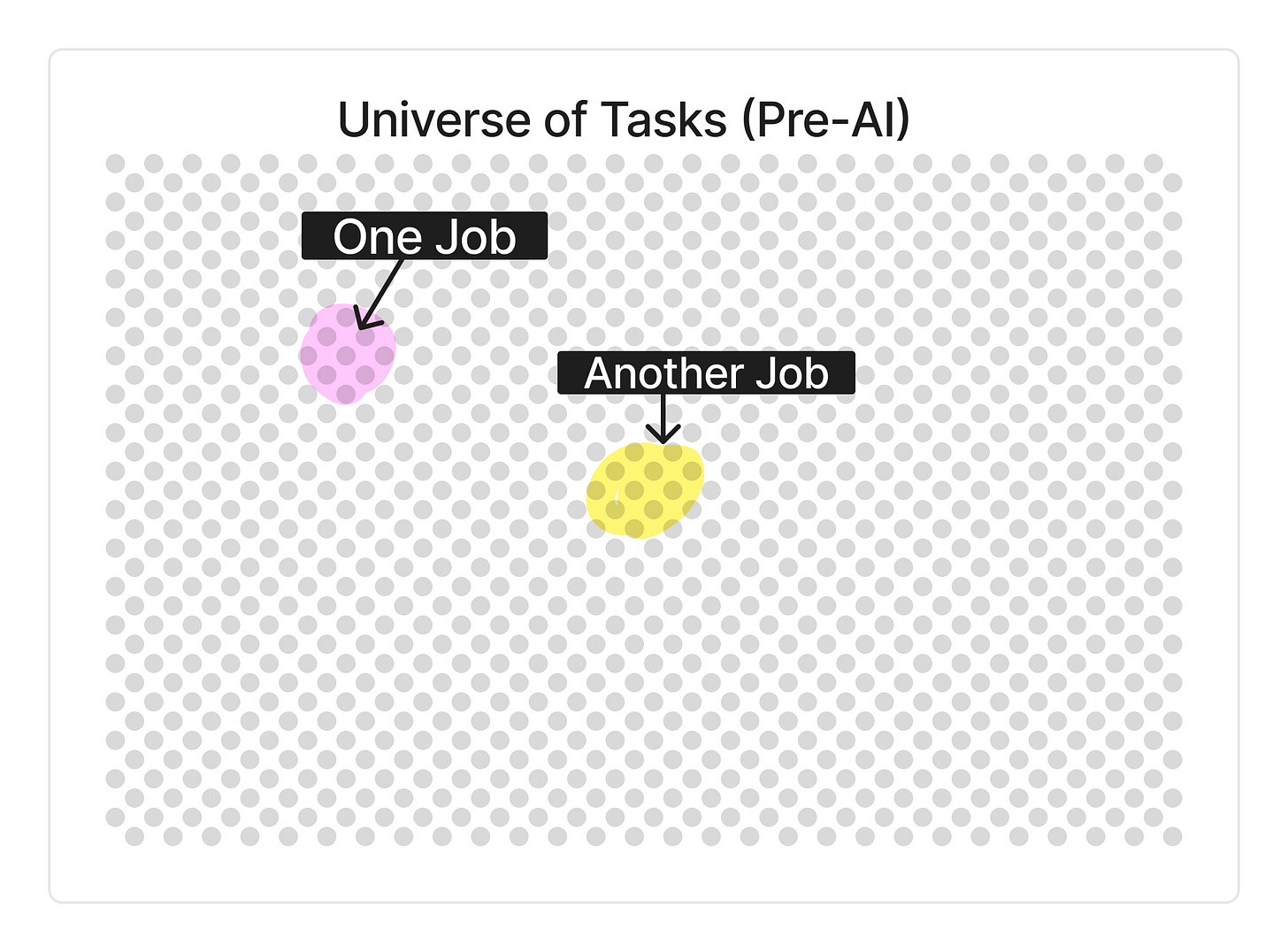

Most of us think about jobs in terms of titles and roles (”management consultant”, “software engineer”, “product manager”). But jobs are actually a bundle of tasks that can be unbunled and rebundled. It has little to do with the title. In the picture below, each grey dot is a task and the pink and yellow bundles are examples of jobs.1

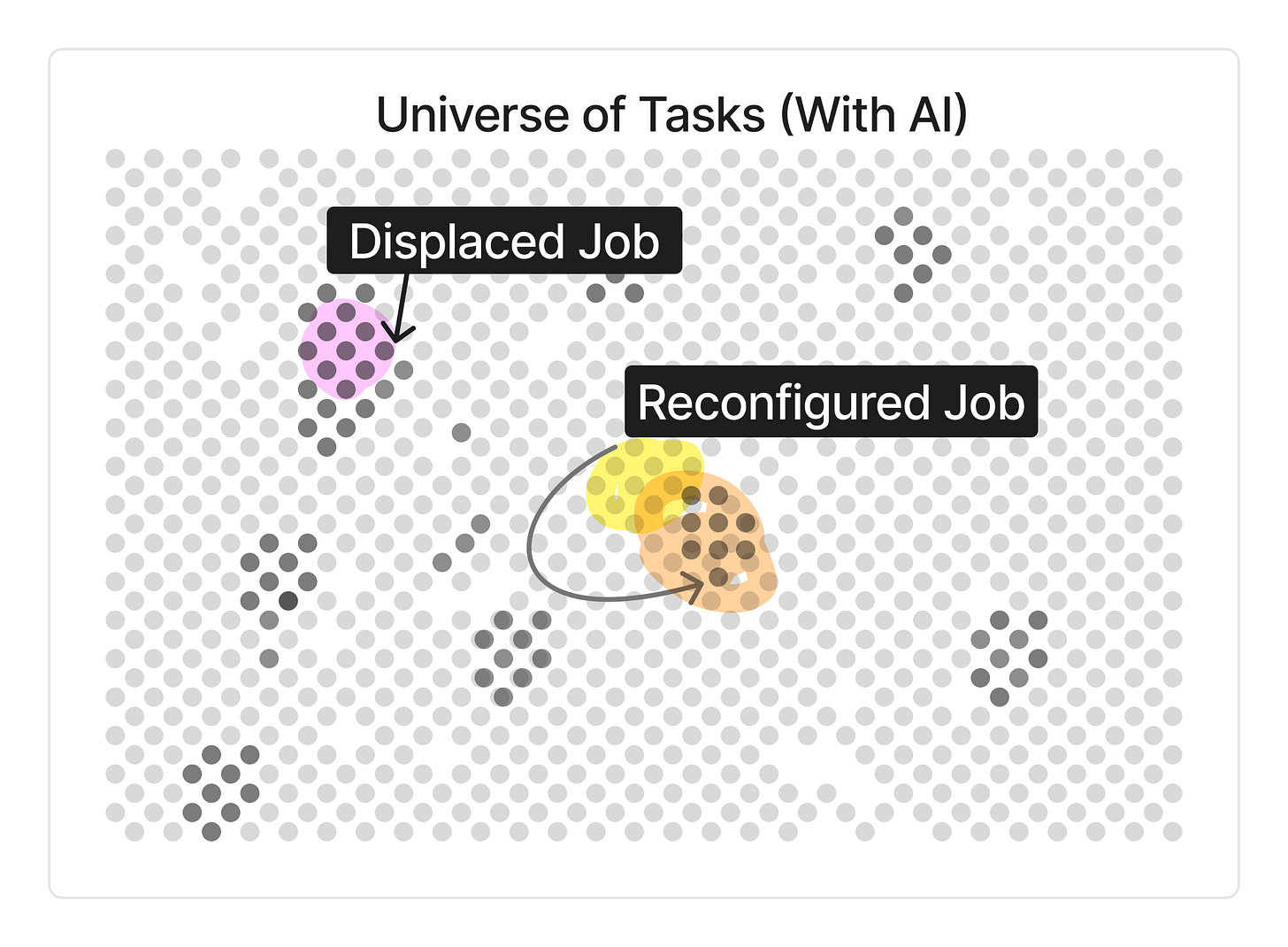

As AI gets better and better, some of the grey dots (pre-AI tasks) will disappear and some dark dots representing fully-AI automatable tasks will appear. As a result, some jobs will be displaced (if all the dots in your previous job become AI automatable) and some jobs will be reconfigured (if you can outsource some tasks to AI and oversee others).

Let’s bring this back to adaptability. I think that in the age of AI, being adaptable means being able to deal with some of those grey dots disappearing and some of the darker dots appearing (system-wide shifts) and the “bundle” of tasks relevant to your job being redefined as a result.

II. The T-Shaped Professional

Now that we’ve established being adaptable = being able to deal with the bundling and unbundling of tasks within a job, how do we prepare for this unpredictable reshuffling of tasks?

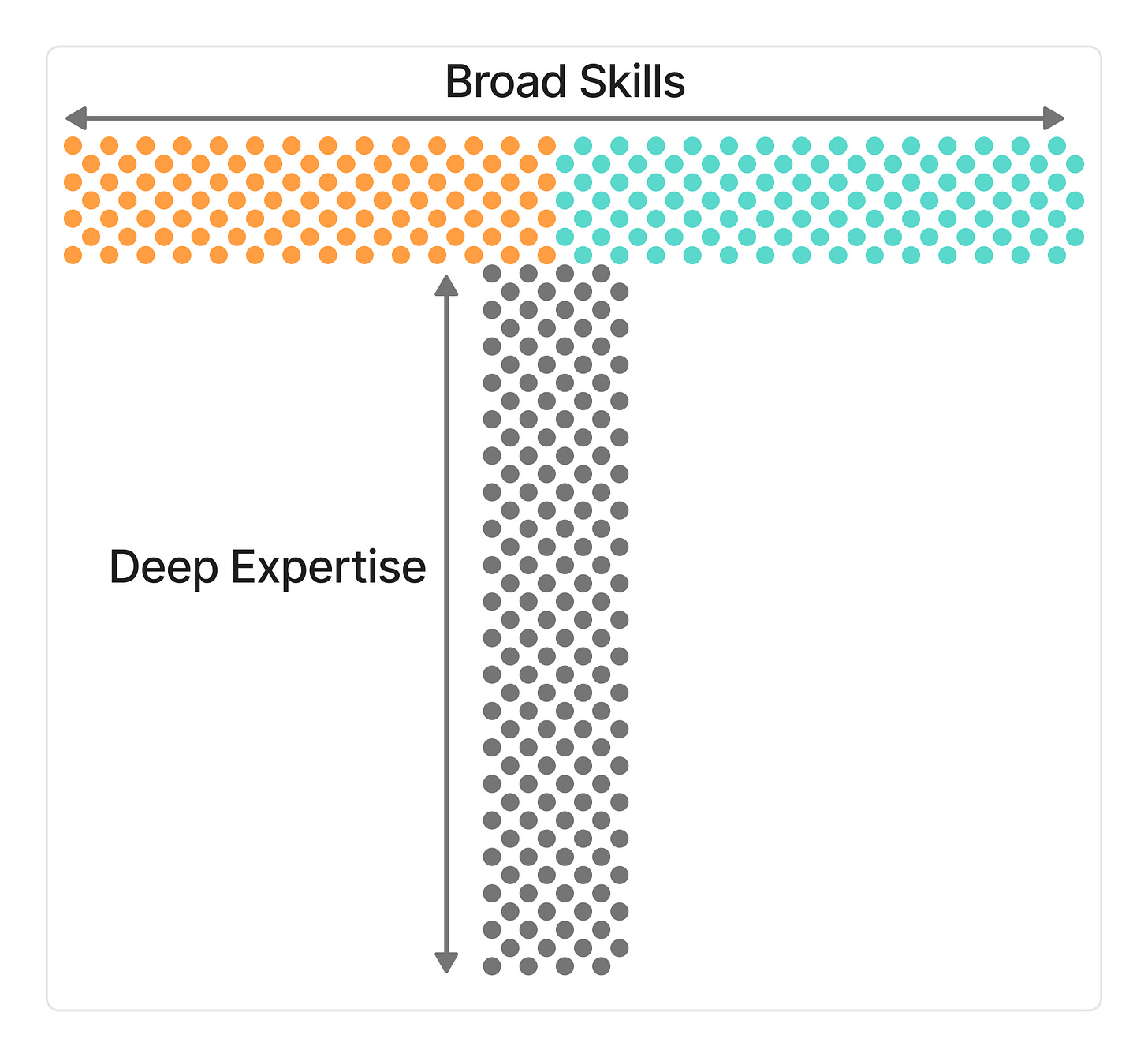

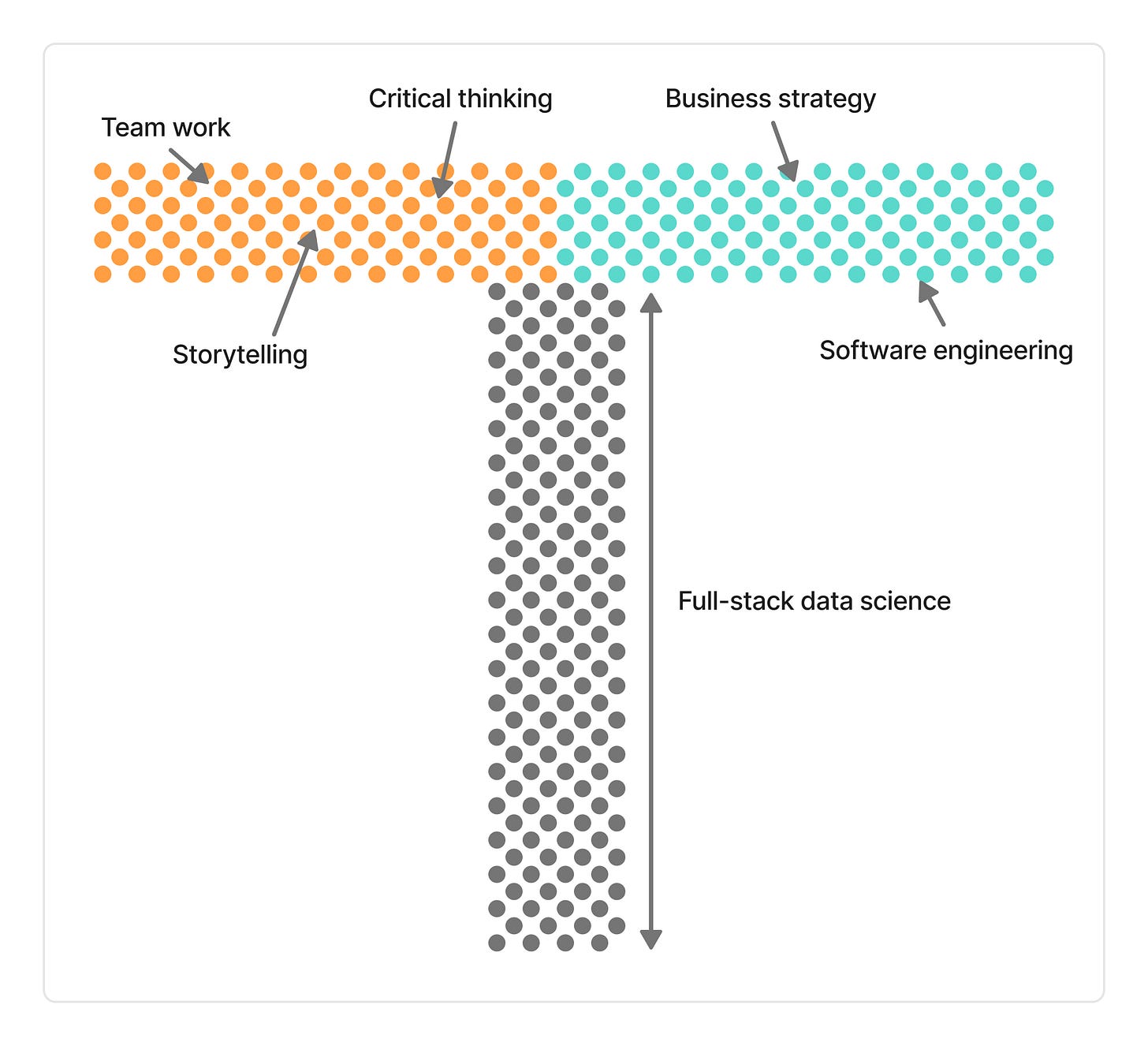

In the 1990s, Tim Brown of the design firm IDEO popularized the concept of “The T-Shaped Professional” (TSP). The T-shape refers to the depth and range of expertise. The TSP is someone who can combine deep expertise in one area (the vertical stem of the “T”) and broad, functional knowledge across multiple disciplines (the horizontal bar of the “T”). Brown contrasted TSPs with “I-shaped” specialists (deep but narrow) and “generalists” (broad but shallow).

The TSP is a specialist with a generalist mindset. And I think this is precisely the sort of thing we need to be adaptable in the age of AI.

You need deep expertise (the vertical) because…

Depth is needed for AI oversight - only with deep expertise can you accurately assess AI outputs, identify errors, know when to override algorithmic suggestions.

Above-average expertise creates value AI can’t match (yet): I think AI’s really good at producing work at the level of an average professional, but it struggles with mastery. It doesn't have the nuanced understanding that comes from years of being immersed in a topic. Depth gives you pattern recognition that AI lacks.

And you need breath (the horizontal) because…

AI excels at specialized, repetitive work within narrow domains. Being confined to one skill set makes you vulnerable when that specific task gets automated.

The ability to pivot is a hedge. As AI reshapes industries, if you have knowledge across domains, you can more easily shift to adjacent areas where your skills are still relevant.

A historical analogy: In the 1920s, 15% of all American women had worked as phone operators. When the technology for direct dialling became cheaper, operator jobs dropped by over half. The job market overall adjusted - women found other roles (mainly secretarial positions that offered similar or better pay). But the women with the most experience as operators took a larger hit because their deep experience in their now extinct job didn’t translate to other fields.2

III. Becoming T-Shaped

Phase 1: Develop Full-Stack Skills

The first phase is about broadening within your core skill cluster. You’ve probably heard the term “full-stack” used for engineers. But this concept can be expanded to other fields. Becoming full-stacked means being proficient across all major components of your domain.

A full-stack engineer doesn't just write front-end code; they handle back-end systems and database management too

A full-stack writer doesn't just craft articles; they understand SEO optimization, content strategy, and basic design principles

A full-stack marketer isn't just doing email campaigns; they're comfortable with social media, SEO (or GEO these days), and paid advertising

To become full-stack, you don’t need to be a deep expert in every component. But you should have enough competence to either execute tasks across the stack independently or effectively collaborate with specialists.

Why bother?

In short, as AI becomes better at automating certain components of a workflow, we need to get better at control and oversight. AI tends to automate specific components within a workflow first. AI writing tools can draft decent content, SEO tools can suggest keywords, analytics platforms can generate basic reports. But they don't seamlessly integrate these elements—that still requires human oversight. A full-stack professional uses AI to handle discrete tasks while maintaining strategic control over the entire process.

This has happened again and again in history. As Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor write in “AI as Normal Technology” (great read):

“Before the Industrial Revolution, most jobs involved manual labor. Over time, more and more manual tasks have been automated, a trend that continues. In this process, a great many different ways of operating, controlling, and monitoring physical machines were invented, and what humans do in factories today is a combination of “control” (monitoring automated assembly lines, programming robotic systems, managing quality control checkpoints, and coordinating responses to equipment malfunctions) and some tasks that require levels of cognitive ability or dexterity that machines are not yet capable.”

Relatedly, look at any senior job posting - they invariably require multiple skills within a cluster because they need to know how to manage the more junior people executing on specific components. For example, nobody becomes Head of Marketing without understanding (and having done) organic, paid, search, and community elements. With AI, each “individual contributor” has an AI-team at their disposal to manage and oversee if they so wish.

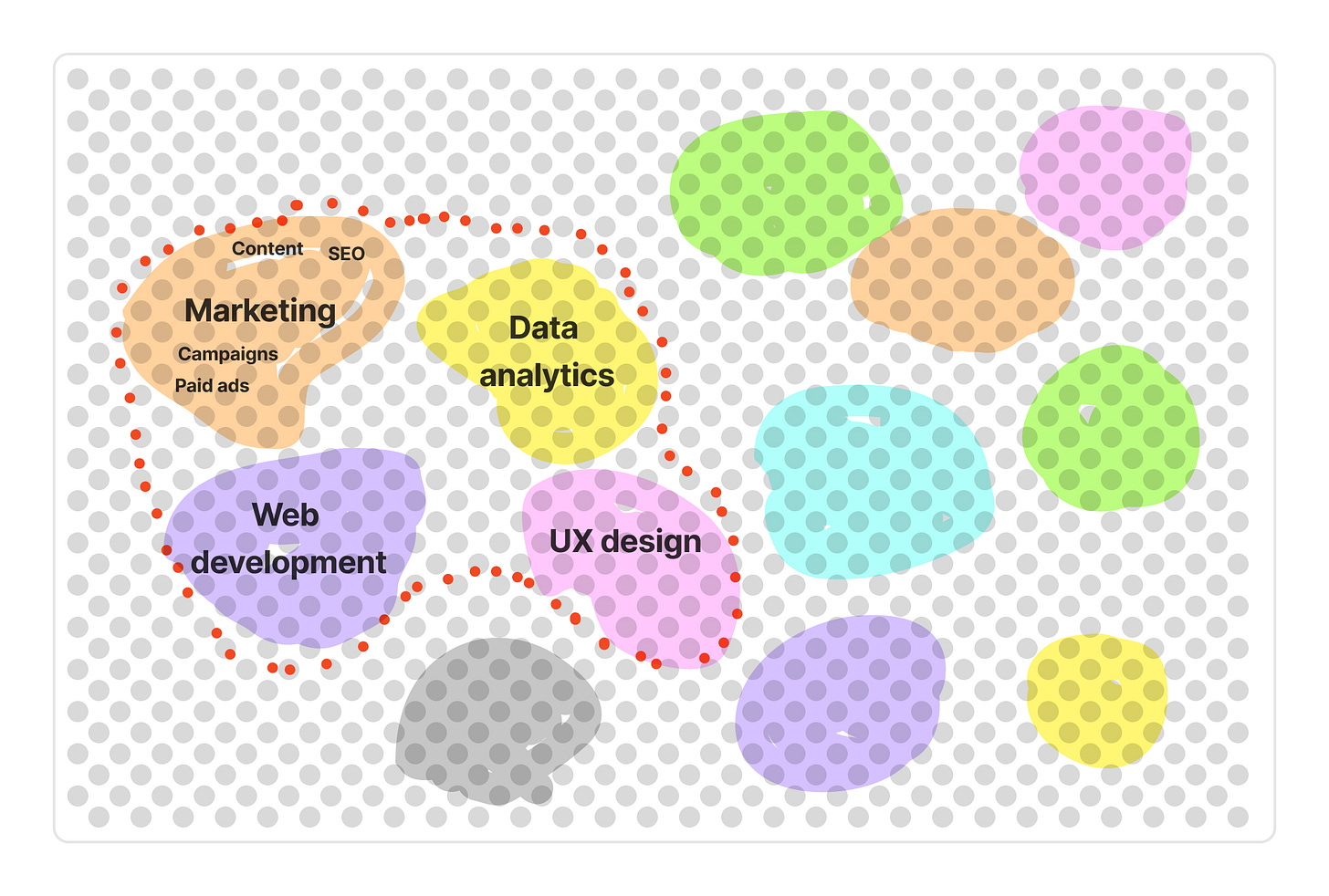

Phase 2: Develop Cross-Domain Skills

Once you’ve established full-stack capabilities in your core domain, it’s time to build the horizontal bar of your T by expanding into neighboring skill clusters. Here, the goal is to strategically learn functional skills from adjacent fields that complement your core expertise.

Some examples:

Marketing professional

Core cluster: SEO, content creation, graphic design, campaign management

Neighboring clusters: Data analytics (for campaign insights), UX design (for content usability), basic web development (for landing pages)

Healthcare professional

Core cluster: Patient care, diagnostics, electronic health record management

Neighboring clusters: Health informatics (for data analysis), medical billing (for financial systems), patient advocacy (for policy knowledge)

Product Manager

Core clusters: User research; A/B testing and product metrics; Market analysis

Neighboring clusters: UX/UI design principles, Technical understanding (enough to communicate with engineers), Marketing strategy (positioning, GTM planning), Data analytics (for product performance assessment), Business modeling (revenue projections, pricing strategy)

Why bother?

Because while AI excels at specialized tasks within a single domain, it still struggles with cross-domain synthesis. If you develop enough cross-domain understanding, you’ll be able to collaborate with specialists from other domains and spot opportunities for synthesis. For example, a developer with UX understanding ensures AI-generated code creates genuinely user-friendly experiences, not just technically correct solutions.

(AI agents are starting to tackle cross-domain tasks, but they still lack the contextual understanding and nuanced judgment that comes from genuine human experience across multiple domains.)

Phase 3: Develop Cross-Functional Human Skills

The final phase in becoming truly T-shaped involves developing universal, human-centric skills that transcend specific domains completely. These are things like: teamwork; storytelling; dealing with people you disagree with; critical thinking; empathy; ethical judgement.

I’ve labelled this as “Phase 3” but these cross-functional human skills are actually foundational human capabilities that should be developed in parallel with your technical expertise. They’re more like the soil in which your T-shaped profile grows, not the final decoration on top.

Again, some examples:

Data scientist:

Core cluster: Full-stack data science capabilities

Neighboring clusters: Business strategy (connecting insights to key metrics and business goals), Software engineering

Cross-functional skills: Storytelling to communicate insights to non-technical stakeholders; Critical thinking to determine which problems are worth solving; Teamwork to collaborate with engineers and business units

Healthcare professional:

Core cluster: Patient care, diagnostics, EHR management

Neighboring clusters: See phase 2 above

Cross-functional skills: Storytelling to educate patients effectively, teamwork with interdisciplinary medical teams, empathy to comfort families, critical thinking for complex diagnostic decisions

Product Manager

Core cluster: Full-stack product management capabilities

Neighboring clusters: See phase 2 above

Cross-functional skills: Storytelling to build compelling product narratives; Leadership to align cross-functional teams; Conflict resolution for balancing competing priorities; Critical thinking for feature prioritization

Why bother?

These human-centric skills sometimes get the bad rap of “soft” skills. But right now, they’re the foundational human capabilities that AI struggles most to replicate. McKinsey projects that demand for socio-emotional skills will rise 26% in the US and Europe by 2030, precisely as automation increases. Again, all of this makes sense - as AI automates more technical work, those who can inspire teams, navigate ambiguity, and make nuanced ethical judgments become more valuable, not less.

IV. Putting it all together

No one can tell you exactly which skills to learn for guaranteed work security in 2030. That’s why Sam Altmann’s response, albeit vague, sticks with me. We don’t want to cling to specific tasks or skills but rather develop the adaptability to deal with change. I think becoming T-shaped gives us a chance to thrive amidst the change.

The jobs that exist today won't be the same jobs that exist tomorrow. Some will disappear entirely. Others will be reconfigured beyond recognition. Many new ones we can't even imagine will emerge. If you can learn to find that prospect more exciting than frightening, you probably already have a T-shaped mindset.

Or, at least, this is what I think as of May 2025. Let’s see if new AI tech changes things up even more.

What do you think?

—

Ines

This is why we see the terms “tasks” (or “what you’ll be doing”) on job ads. Similarly, the ONET database maintained by the US Department breaks down each occupation into “tasks” and “work activities” (along with things like skills, knowledge, and abilities needed for the job).

A note on what a T-shaped professional isn't. First, a T-shaped professional isn’t a polymath (someone who pursues mastery across diverse domains like science and art). Second, it's not necessarily the case that the vertical stem of the T represents “hard” skills (e.g. coding) and the horizontal stem of the T represents “soft” skills (e.g. teamwork). The horizontal bar (as we see in examples below) often includes technical skills too. Also, the vertical stem can be “soft” - in some roles, the deep expertise is a soft skill - e.g. a therapist might have deep expertise in counselling with breath in tech tools for telehealth (hard).

girl i would have thought you had like 30k subscribers. you should, because your insights are well-founded relevant and written in a concise yet highly informative manner. keep slaying.

Great insights Ines! The big takeaway for me is focusing on developing cross-domain skills. AI is good at specialized tasks within a single domain, but cant do cross-domain synthesis. The thing is, the more I do this, the more value I get out of AI.