how to build your information advantage

Your feed is your competitive edge or your glass ceiling

You’ve probably heard Jim Rohn’s famous insight: “you are the average of the five people you spend the most time with”.

For knowledge workers, there’s an even more relevant spin: You are the average of the five information sources you consume the most.

If you’re always consuming the same stuff, you’re unlikely to have novel thoughts. If you’re consuming what everyone else in your field consumes, you’re likely to be thinking what everyone else thinks. As writer Haruki Murakami writes, “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

As knowledge workers, our job is fundamentally about consuming information and transforming it into insights, decisions, and solutions This means that our podcast queue, newsletter subscription, Instagram feed aren’t just entertainment. They’re also your raw materials for thinking.

Our feed quietly shapes who we are as people, how interesting we are in conversations, how creatively we approach problems, the opportunities we’re able to spot, and eventually the opportunities that we can take advantage of.

I’m reflecting on all this because lately my information diet has felt same-y and stale. I’m still reading new books but when the third self-help or business book repeats the same message, I feel like I’m eating empty calories. I listen to podcasts but sometimes more as background noise rather than genuine engagement. And when I chat with other people in my field, it seems like we’re all referencing the same stuff, feeding from the same pool of sameness. It’s a bit like living on white bread for three meals straight. We’re fed, but not nourished.

If original thinking today shapes opportunities tomorrow, I’m beginning to wonder this “information sameness” is limiting us somehow. So, I want to dive into (1) why this feeling of “sameness” is happening and (2) more importantly, what we can do about it.

Why it’s hard to escape “sameness”

First thing to say is that it seems like this is a broader problem. There’s indeed evidence that things look increasingly look, sound, and feel the same:

A 2019 analysis by Hooktheory of over 1,300 hit songs found that harmonic variety has collapsed, creating what critics call the “nursery rhyme effect.”

Adam Mastroianni writes that “pop culture has become an oligopoly” - books, movies, and music increasingly controlled by a shrinking set of players who stick to what already works. So we get Superman, again. Batman, but darker.

Erifili Gounari writes “everything sounds the same, and it feels incredibly tiring and boring to read dozens of posts every day that were just written to check a box” and I’ve seen other people echo this.

Carl Hendrick writes about the “ultra-processed mind” - the psychological parallel to an ultra-processed food diet. Carl writes about it in the context of reading, but I think it extrapolates to all kinds of information/media consumption.

Let’s dissect why this is happening.

It’s easy to blame the algorithm, social media platforms, and the entrepreneurs and engineers behind it. But I don’t think cultural sameness is the fault of any single villain. It’s an emergent property of a complex system.

When you reach for that bag of chips (parallel: scroll TikTok) instead of preparing a home-cooked meal (parallel: read a challenging book), it’s not just because food companies engineered those chips to be irresistible. It’s also because you’re tired and a little stressed, because the chips are conveniently within reach, because your body has developed a taste for salt and fat, and because preparing a home-cooked meal requires more effort. You munching on that bag of crisps result from a convergence of factors: corporate incentives, your biological wiring, environmental cues, the path of least resistance.

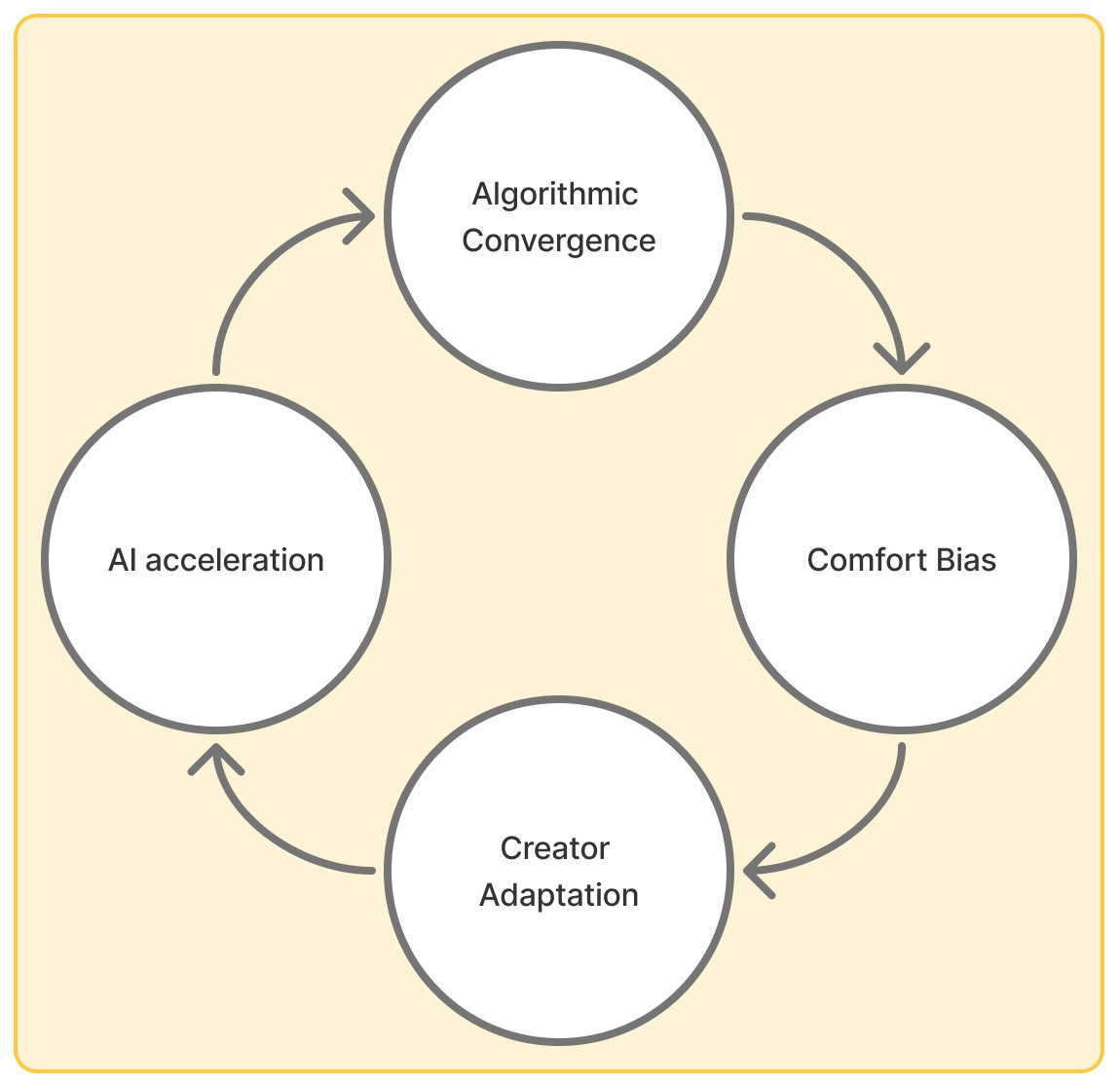

Information consumption works in a similar way. The “sameness” people have documented comes from at least four intersecting forces, each reinforcing the others.

(1) Algorithmic Convergence

The algorithms that feed us - LinkedIn, Spotify, YouTube, Netflix - don’t optimize for enlightenment. They optimize for engagement. That means: give you more of what you already liked.

Doug Shapiro explains it beautifully: algorithms combine collaborative filtering ("people similar to you enjoyed this, so we think you might too) and predictive models ("this video shares attributes with stuff you’ve liked before, so you might like it too”). That’s how they learn to keep you watching, scrolling, consuming.

(2) Comfort Bias

But algorithms don’t exist in a vacuum. When I watch another similar YouTube video, add another familiar song to my Spotify favorites, or grab another easy-to-read rom-com on Kindle, these actions train the algorithm.

We think we’re making active choices. But, often, we’re reinforcing unconscious biases - toward what’s familiar and frictionless. The algorithm isn’t evil. It’s obedient. It responds to what we train it on.

(3) Creator Adaptation

At this point, the algorithms have established what “viral success” looks like. Creators have a stark choice: adapt or disappear.

So, an entire industry has emerged around decoding what works. LinkedIn creators have go-to hooks (“Hard truth:” followed by a provocative claim). YouTube thumbnail designs categorized by which facial expressions generate the highest click-through rates. Screenplay structures that break successful films into precise formulas with page counts for each story beat.

I personally love a good ol’ template (and I’m the beneficiary of many of them). But when these templates dominate, the aperture for creative possibility narrows. We sand down the weird edges and simplify complex ideas to fit the mold of what we know works.

(4) AI Acceleration

Oh, and of course, how can we forget AI in 2025? Today’s AI, trained on vast amounts of human-generated content, excels at synthesizing the “average” - which potentially amplifies the problem of sameness if not used innovatively.

In a 2023 study, researchers recruited ~300 participants to write short stories with and without AI assistance, then had evaluators judge creativity and engagement. AI helped less naturally creative writers produce more creative stories. But collectively, the AI-assisted stories were much more similar to each other than the purely human-generated content. AI introduced an “anchoring effect”, subtly pulling individual creative minds toward common reference points.

Individual gain. Collective flattening. That's the AI creativity paradox we face: AI can make individual creators better, faster, and more articulate, while simultaneously making the overall cultural landscape more homogeneous.

How to Build Your Information Advantage

We used to associate intelligence with accumulation. Who knows the most facts, who has the most degrees, who’s read the most books.

But that model died when information became infinite.

Intelligence today isn’t about knowing the most. It’s about filtering the best.

So, the question becomes: How do you build an information diet that creates advantage instead of conformity?

Let’s first get clear about what this doesn’t mean. This isn’t about rejecting popular content out of snobbery or chasing obscurity for its own sake. Good filtering isn’t about being contrarian. (Why should anyone have the right to decide what constitutes “good” culture/ media/ information anyway?) It's about intentionality. It’s about being thoughtful. It’s about becoming the architect of your own cultural, intellectual, and spiritual development rather than a passenger on the algorithm’s ride.

Here are a few principles I’m experimenting with in an attempt to avoid the sameness spiral and feed my mind with less ultra-processed food.

(1) Spend more time choosing what to consume

I tend to consume on autopilot - playing the first podcast in the queue, clicking the top link on YouTube, reading whatever newsletter hits my inbox that morning. Instead, I want to spend a bit more time curating what to consume.

Some recent examples:

I had a few long drives recently. Instead of just autoplaying my Audible or podcast queue, I spent a few minutes before the drive asking, “What problem am I trying to solve this week?” Then, I looked for stuff that offered different angles on that problem. It was worth it.

I started a “To investigate” list in Apple Notes that I add to throughout the week. On Sunday, I evaluate what deserves my attention the following week.

(2) Time-diversify your inputs

New ≠ better. Modern platforms prioritize recency over insight, but ideas that endure do so for a reason.

Sheehan Quirke (aka The Cultural Tutor) once said: “I don’t read anything published in the last 50 years… If you read what everybody else reads, you’ll say the same things as everybody else.”

This is a bit extreme, but I like the spirit of it. Some examples of how to put this in practice:

Build a “100-year feed”: Each month, consume one book, essay, or lecture written before 1925.

Follow curators who unearth forgotten brilliance / make old stuff accessible to a modern audience (some favourites on Substack:

, ; ’s lifetime reading list)

(3) Topic-diversify your inputs

Just as financial advisors recommend portfolio diversification, your information consumption needs diversity. I’m experimenting with a 50/20/20 rule:

50% “usual” sources

25% adjacent disciplines to create unexpected connections

25% completely unrelated domains to hopefully develop unique perspectives

(Example: A salesperson I know took an improv class. He says his close rate jumped 40% because he learned to build on opposition rather than fight it in high-stakes deals.)

(4) Go deeper, slower

A few years ago, I was super inspired by people who could read 50-100 books a year. I’d attempt a reading goal like that, but subsequently felt like I was wolfing down pages for the sake of hitting an impressive number. I’d forget the core insights within a week as the (oftensimilar) books blur together into a content smoothie.

These days, I just want to focus on fully understanding and internalizing 10-20 well-selected books each year. So, it’s time to go slower but deeper by giving myself permission to:

Return to a single essay or book multiple times.

Read one chapter, then close the book for 24 hours. Let the ideas percolate. Connect them to current challenges.

Spend time writing a response to what I’ve read - what’s the core thesis? what do I agree with? what don’t I agree with?

(5) Escape the feed

The feed is designed to be frictionless. Filtering requires friction, not just being carried to wherever the algorithm decides.

Things I’m doing to (occasionally) escape the feed

Using tools like Readwise, Pocket (RIP), or Notion to pull content into an “off-the-feed” queue

Blocking time to read inside that queue, not wherever the algorithm points

Your Filter is Your Future

Jim Rohn told us we're the average of the five people we spend the most time with. But in a busy week, many of us spend more time with our feeds than in-person time with our friends - which means the five sources shaping your thinking matter as much as the five people in your living room.

Your information diet can be your competitive edge or your glass ceiling. Every algorithm-served video you watch, every article you mindlessly skim, every podcast you passively consume, is shaping tomorrow’s thoughts. And tomorrow’s thoughts shape next year’s opportunities.

So every few months, I’m encouraging myself to audit my information diet. List the books I’ve read. The YouTubers I watch. The podcast I listen to. If I removed one of those sources and replaced it with something else, would it matter? It’s a little scary when there are more “no”s than “yes”s.

In a world where information is infinite and original thinking is scarce, your filter is your future. Design it like your future depends on it. Because it kind of does.

Loved the article!

Just like how professional chefs say “The better the quality of your ingredients, the better the dish will be”, similarly “the better your content diet, the better your creation will be”

I use chrome extensions like “Unhook” which doesn’t show YouTube recommendations and sidebar, which helps with consuming content intentionally.

Wonderful article - so insightful, as always! Love your writing and how you incorporate evidence backed research! Great one I’ll definitely share!

Nicole x